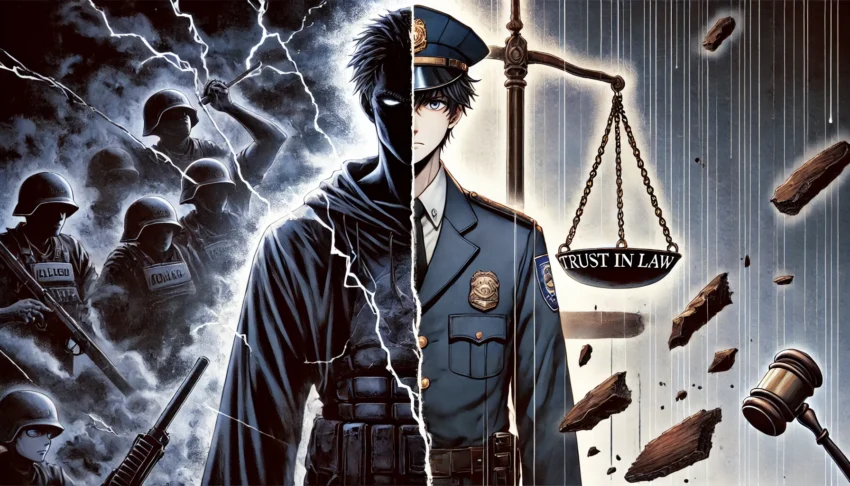

Trust between law enforcement and the public is essential to a functional society. Without it, the cooperation required for effective policing deteriorates, leading to negative consequences for both citizens and officers. However, a single Supreme Court ruling in 1969—Frazier v. Cupp—has systematically eroded this trust by granting police the legal right to deceive those they are meant to protect. This decision sparked a dangerous shift, allowing citizens to assume that anything a police officer says could be a lie and any “mistake” an officer makes is excusable. The fallout has been profound, fundamentally damaging the relationship between law enforcement and the communities they serve. Until this ruling is overturned, the only rational approach for citizens is one of skepticism toward what officers say. Trust is what we need in our police—this article explores how Frazier v. Cupp has irreparably harmed that trust and calls for urgent legal reform.

Frazier v. Cupp (1969)

The Frazier v. Cupp case set a legal precedent with long-lasting consequences for the relationship between police and the public. Martin Frazier, a murder suspect, was falsely informed by police that his cousin had already confessed and implicated him. This lie led Frazier to confess, and that confession was used against him in court.

When the case reached the Supreme Court, the justices ruled that the confession was admissible despite the police deception. The Court argued that police deception was not inherently coercive and could be a legitimate tool during interrogations. This ruling effectively legalized the practice of police lying to suspects and set a precedent that has shaped law enforcement tactics for decades.

The decision in Frazier v. Cupp granted police officers broad latitude to use deception during investigations. Many wrongful convictions, such as those of the Central Park Five (1989), the West Memphis Three (1993), and Henry Lee McCollum and Leon Brown (1983), involved police deception. These cases, where convictions were overturned decades later, highlight a critical issue: when deception is sanctioned as a law enforcement tool, it endangers innocent lives and erodes public trust in the institutions meant to protect them.

The Police’s Position: Justifying Deception

From the perspective of law enforcement and the Supreme Court’s reasoning in Frazier v. Cupp, police deception is often defended as a necessary crime-fighting tool. The Court argued that these tactics are not inherently coercive and, when used judiciously, can be effective in eliciting confessions from suspects who might otherwise remain silent or deceptive. Proponents argue that the ends—securing convictions and maintaining public safety—justify the means. In complex cases, where evidence is circumstantial or suspects are uncooperative, deception is seen as a legitimate and sometimes indispensable method for uncovering the truth and bringing offenders to justice.

Moreover, law enforcement agencies argue that the ability to deceive during interrogations levels the playing field. Criminal suspects may lie, withhold information, or manipulate the truth to avoid conviction. Allowing police to use deception counteracts these tactics, giving officers a strategic advantage that can be critical in breaking down the defenses of guilty suspects. In this view, deception is a pragmatic approach that serves the greater good, ensuring that criminals do not escape justice due to a lack of cooperation or direct evidence.

The Flaws in This Justification

While this reasoning may seem compelling on the surface, it falls apart under scrutiny. The justification for police deception hinges on the assumption that such tactics primarily target guilty individuals and that the benefits of securing confessions outweigh potential harms. However, this assumption is fundamentally flawed. Deception can, and often does, ensnare innocent individuals, leading to false confessions, wrongful convictions, and profound miscarriages of justice. The cases of the Central Park Five, the West Memphis Three, Henry Lee McCollum, and Leon Brown illustrate how deceptive practices can lead to devastating outcomes for the innocent.

Furthermore, the notion that deception serves the greater good ignores the broader societal impact of eroding public trust. When citizens learn that police are legally permitted to lie, it undermines the legitimacy of law enforcement and sets police against citizens. Any rational citizen’s response to contact with the police is justifiably fear and distrust, since that officier has the right to legally lie and those lies are likely to result in the citizen losing their freedom.

Finally, the idea that deception “levels the playing field” is problematic because it ignores the inherent power imbalance between police officers and suspects. Officers have the backing of the state, access to extensive resources, and specialized training in interrogation techniques. Suspects, by contrast, may lack legal knowledge, experience intense stress, and be unaware of their rights. In such a context, allowing police to lie exacerbates this imbalance, making it easier for law enforcement to manipulate vulnerable individuals into false confessions.

The Intersection of Legal Complexity and Public Distrust

In his book Overruled: The Human Toll of Too Much Law, Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch articulates a growing concern that the sheer volume and complexity of laws and regulations have left ordinary Americans feeling overwhelmed and alienated from the legal system. Gorsuch argues that when laws become too numerous and convoluted, they not only burden individuals but also erode trust in the institutions meant to serve them. He posits that too much law can be as detrimental as too little, impairing the very liberties the legal system is supposed to protect.

This critique aligns closely with the issues surrounding the Frazier v. Cupp ruling and its endorsement of police deception. Just as the proliferation of laws can lead to a sense of entrapment and distrust among citizens, the legal sanctioning of deceptive practices by law enforcement exacerbates public wariness of the entire justice system. When people cannot trust that they will be treated honestly by those in power—whether due to an overwhelming number of laws or the legal permission to lie—their faith in the system naturally deteriorates.

Gorsuch’s argument underscores a fundamental principle: the law is meant to protect and empower, not to ensnare or deceive. When the legal framework becomes a tool of manipulation—whether through excessive regulation or sanctioned deceit—it undermines its own legitimacy. The public’s trust, once broken, is difficult to restore. Just as Gorsuch calls for a reassessment of the regulatory state, there is a pressing need to reconsider the ethical and legal standards that govern law enforcement practices. Only by addressing these deep-seated issues can the law regain the public’s trust and fulfill its role as a guardian of liberty.

Conclusion

The Frazier v. Cupp decision has had devastating consequences for public trust in law enforcement. While deception may sometimes lead to confessions, it comes at a steep cost—innocent lives and the trust that is the foundation of effective policing. To rebuild this trust, legal reform is essential. Only by reevaluating and overturning decisions that permit deception can the relationship between law enforcement and the public begin to heal, restoring the faith necessary for a just and functional society.